A Compromise

Hopefully

the image below looks a bit like a collybita Chiffchaff (Phylloscopus c. collybita). It is in fact a colour composite created using a new conceptual

template which I call a Colour Profile (CP).

Why?

As outlined

in my introduction to colour profiling (HERE) there are many challenges to

consistently presenting and describing colours from digital bird images. While it

is possible to reasonably accurately and consistently capture the hue of

colours in nature, capturing the saturation and luminosity of colours

accurately using a digital camera is confounded by the difficulty in obtaining

an accurate exposure. By creating this CP template I have eliminated the

need to capture saturation and luminosity at all because these are pre-sets provided

for in the template.

As to the

broader question of why we might need or use these templates in the first place, I specifically

chose Chiffchaffs as my first template because of the ongoing interest in rare

Chiffchaff taxa in Western Europe. A complete understanding of the colour variation

within this group is still quite elusive it seems, such that some of the very

pale Chiffchaffs which until recently were thought to be possibly P. c. abietinus were found

to be genetically P. c. tristis yet we know that many birds giving the classic tristis call are often mid-brown in colour and not especially pale. Obvious

questions that need answering include, how variable are tristis? Are abietinus occurring in Ireland and Britain and how do we distinguish abietinus from tristis and collybita in the field? Could there be other hidden taxa involved? This tool might help us

figure some of these things out.

Many interesting online discussions

about colour in Chiffchaffs appear to break down when the question of camera

exposure and white balance comes up. The intention of this template is to

apply a standard, reliable methodology and help get past the photographic

questions to start to catalogue and organize digital images of vagrant Chiffchaffs into some

kind of order mainly based on colour hues.

How?

Here are

the pre-requisites required to use the CP template to create a colour profile for

a specific Chiffchaff.

(1) You must use an X-rite Colorchecker Passport to create a DNG profile for your camera. The template won’t work

reliably without one. The main problem is cost – roughly €100/$100

for the X-rite. Note the software used to create DNG profiles is

available free from the X-rite website so all you may really need to do is borrow an X-rite

colour checker passport for a few minutes to make images of it with your camera

and later create your own DNG profiles back at home. 5 birders interested

in this project, €20 each – if you catch my drift?

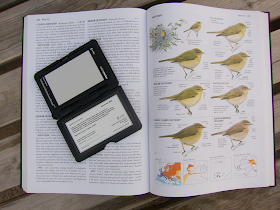

X-rite Colorchecker Passport (formerly Gretagmacbeth) with

Dan Zetterström's Chiffchaff plate from the large format Collins Bird Guide, 2nd edition.

(2) Anyone going into the field to take

photos of a Chiffchaff with the intention of creating a colour profile will

need to bring with them a white balance card (called a grey card). The X-rite colorchecker

passport comes with one but they can be purchased separately and much more

cheaply than the full passport. X-rite is just one manufacturer of grey cards. The make should not matter provided it is actually properly

neutral. Beware grey cards that are actually not neutral at

all. If you have purchased a grey card and you want to verify it

is neutral take a picture of it with an X-rite grey card along

side (if you can borrow one). Correct the white balance in the image using both and there should

be no difference in colour temperature recorded. If there is a difference then one or other of the grey cards is a dud! Lastly,

all pigments are subject to deterioration over time. All calibration

cards will need replacement every few years. This applies equally to the colour checker as it applies to the grey card. X-rite recommend replacement every couple of years but it all depends on usage I guess.

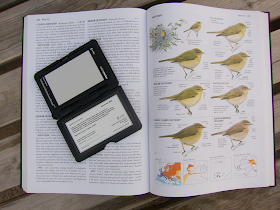

X-rite Grey Card with Dan Zetterström's

Chiffchaff plate from the large format Collins Bird Guide, 2nd edition.

Note how similar this image and the one above are.

All that was required to process these images was the sampling of the white balance

patch and the selection of the correct DNG profile.

With two mouse clicks both images were perfectly colour calibrated.

Reason enough to purchase and use this product I think.

(3) Your camera must be able to shoot RAW format files. You need RAW anyway to create a DNG profile and you also need to be using Camera RAW or an equivalent software package to apply the DNG profile to

your images. DNG profiles can't be applied to JPEGs. It is also the best place to apply your white balance

correction to all your images in one go.

Warning, JPEGs are compressed files – colours are also compressed by the process so there is a potential loss of colour accuracy with the switch to JPEG. Try to

work with PNG images rather than JPEGs to avoid the problem of lossy

compression.

(4) In the field you must ensure that

your subject is out in the open and not under a foliage canopy or near some

other source of “unnatural” illumination. The only way of properly

sampling the colour is by illumination from day light. A

bird sitting in the shade on a sunny day is fine too so long as the grey card is also positioned in the shade for reasons explained HERE.

And, as stated, getting an accurate white balance is essential – don’t forget

to take photos of the grey card, positioned appropriately during your

session. If you have forgotten to photograph the grey card or the light

has shifted during the shoot you are back to square one.

(5) So you arrive back home having

successfully photographed a confiding Chiffchaff in RAW format files and you

have a good, accurate white balance image in the mix as well. Happy

Days! Open up your images in Camera Raw or a similar raw editing software

package and select a white balance standard image plus a series of good,

representative shots of the Chiffchaff. First white balance all the

images by reference to the image you took of the grey card, then apply the DNG profile

correction to each image on top of that. You now should have a properly colour-standardised set of images of the Chiffchaff which you photographed. The

hues in your images should be consistent and very accurate to a professional

standard.

(6) Open up these images from Camera Raw in Photoshop

Elements or whatever software you use and save them as PNG files without any further

correction (not JPEG files as explained above).

(7) Next open up the Chiffchaff CP

template in MS Paint, Photoshop or whatever image editing software you

have. Also separately open up one or more of the properly colour-standardised

PNG images of your Chiffchaff. Now it is time to sample the colour from your digital images and translate those colours to the CP. Start perhaps by sampling a properly exposed area

of the bird’s mantle (refer to my sampling technique HERE). A properly

exposed patch of colour is one which is well illuminated and is neither under nor

over-exposed. Avoid sampling an area which was obviously in shade (eg.

the rear mantle, shaded by the wing tip) - it’s white-balance and therefore its

hue may not be correct. Don’t forget to postarize the colour sample then

paste the postarized sample into the box linked to the mantle. Sample the

colour with the dropper. I recommend using the MS Office postarizing tool called Cutout for now if you can access it. I will need to validate other postarizing tools against Cutout to make sure they all perform the same and arrive at the same colour hue. If anyone intends using a different postarizing tool and want to validate it please get in touch.

(8) The next bit is vital, you must

change the saturation and luminosity settings for that colour to those listed in

the template. Having set these fill the sample and the rest of the box

with the new colour. I have set up the template in such a way that it

will “pump” the colour around the template so to speak and fill in the

necessary areas of the bird automatically.

(9) You will note that I have left two

optional saturation and luminosity pre-sets for the mantle colour. One is

based on the typical characteristics of a mid-toned collybita-type image.

The other suits a typically pale tristis-type. This is where I have

allowed for a small bit of subjectivity. The fact is that we often

encounter birds which appear in life to be exceptionally pale and ghostly but

this doesn’t translate well in photographs due to camera exposure and perhaps also dynamic range limitations. Here is an opportunity to restore some of the ghostly

distinctiveness of a bird without compromising the CP template too much.

Note I have also done this for other sample points within the template.

(10) In the case of the fringes of the

remiges and rectrics I have removed the option to sample and paint these

parts of the template and simply given some pre-set options for hue, saturation and

luminosity. The reason for this is that it is extremely difficult to accurately

sample colours based on so few pixels or micro-structures as one might call them - like these feather

fringes for example. I don’t think this is too much of an issue here as I don’t think

the exact colour of these fringes is critical for

identification. I’m open to correction on this point of course and can add more hue

options here if required.

(11) Having worked through all the

sampling points and painted your CP template the work is done. I would

recommend filling in the hue boxes with text just to confirm the values you

arrived at. Should the profile ever be saved as a JPEG or some other

lossy file by accident the actual colours may deteriorate as a result. At least if

the hues are properly recorded in text in the image it would be easy to recreate

the image exactly as before using the original template. I think it is important to add some additional text in the notes section provided including the

date and location the bird was photographed plus a record of any calls

heard, unusual plumage/colour characteristics noted etc. Also important to add validation information including details of the DNG profile and grey card used. When it comes to

maintaining files for verification purposes later I would recommend storing the CP

together with the RAW and PNG images of the bird used to make the profile including the

white balance image used.

Validation

of the method and template

This

concept is in its infancy. I am hoping that the validation of this method

will come about through the trial and error of myself and others interested in

having a go at using it. I will also set up a validation page on the blog and populate it with various information as I gather it.

(1) I am confident that the colour

standardisation method is excellent for providing accurate and consistent hue

values – professional photographers who use X-rite colorchecker passport

can’t be wrong. Remember we are not talking about recorded colours as the

human eye sees them. This is about using a benchmark to be able to study colour variation with the help of a professional standard.

(2) By taking saturation and luminosity

out of the equation we no longer need to worry about these scales. It makes the

task of creating the colour profile so much simpler.

(3) I am conscious that the template

itself needs some work. I have created REV. 1.0 and put it out without

much fine-tuning for some comment and assessment rather than continuing to work

on it. I would ask those who are far more familiar with Chiffchaff taxonomy

to take a look at the sampling points I have chosen and advise me if I need more

(or less). For instance, is it enough just to have two options for

Hue/Sat/Lum of the fringes of the rectrices and remiges. Should I split the

primary fringes from the secondary and/or tail fringes to have the option to

colour these all separately or is it enough to have all of these lumped

together as one sample point? Should there be more (or fewer) options for

colour the supercillium or greater coverts bar for instance. Is leg colour relevant/necessary? That said,

this needs to be as simple a tool as possible to work with. Otherwise birders will not bother with it. I would hope that an average person,

reasonably familiar with the tool should be able to process images of an

individual Chiffchaff and create a finished colour profile all in under 10 minutes.

(4) I have intentionally blurred the

wing formula as it is not relevant to this profile. This is all

about colours, not structural morphology. Whether the wing formula

is accurate or not is irrelevant. As stated above, the image at the top of this post may look like a collybita Chiffchaff but it is merely a representation of a Chiffchaff type. For that reason, I hope that this will be just

as useful a template for looking at Iberian, Canary Islands or Caucasian Mountain Chiffchaff colour

profiling as it is for Common Chiffchaff taxa. Willow Warbler and other less closely-related species would be a stretch for this template.

(5) Next I hope to create a template for

Lesser Whitethroat taxa, another remarkably challenging and interesting complex

with various taxa reaching Western Europe.

(6) Lastly just to point out that I

would hope to have a final Chiffchaff template complete before September 2014

so that it can be used without further modification this coming autumn and

winter when hopefully there will be plenty of rare Chiffchaffs about to sample and profile. If

you have an interest in getting involved with this project please contact me. Hopefully I can help you get your DNG profile set up and you can

be practising using your grey card and having a go using the

Chiffchaff CP in its current draft. For those with an intimate knowledge

of Chiffchaff taxonomy I would love to hear what you think of the CP template and

what tweaks if any you think it needs.

(7) Finally, if there are any birders in North

America interested in creating a CP for a species or complex from that continent

please get in touch. I might be able to help.

Download

The template is available for download and use at the link below. If you are using it I would greatly appreciate your feedback.

Chiffchaff CP Rev 1.0 (c) Mike O'Keeffe

Update March 2015

It has taken me a long time to connect with a tristis-type Chiffchaff.

HERE is a spring comparison of a

collybita versus a pale tristis-type.

.gif)